CAREY THEOLOGICAL COLLEGE

STRENGTHENING MARRIAGE: BRIDGING EMOTIONAL CUTOFF

Doctoral Thesis Project Strengthening Marriages BEC (pdf)

BY

EDWARD ALLEN HIRD

A Doctor of Ministry Project submitted

In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry

Vancouver, British Columbia

May 2013

CAREY THEOLOGICAL COLLEGE

DOCTOR OF MINISTRY PROGRAM

The undersigned certify that they have read, and recommend for acceptance a

Doctor of Ministry Project entitled

STRENGTHENING MARRIAGE: BRIDGING EMOTIONAL CUTOFF

Submitted by EDWARD ALLEN HIRD

In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MINISTRY.

__________________________________

Dr. Patrick J. Ducklow (Supervisor)

__________________________________

Dr. James J. Ponzetti, Jr.

Date: May 26th 2013

CAREY THEOLOGICAL COLLEGE

RELEASE FORM

NAME OF AUTHOR: Edward Allen Hird

TITLE OF PROJECT: Strengthening Marriage: Bridging Emotional Cutoff

DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY

YEAR THIS DEGREE GRANTED: 2013

Permission is hereby granted to the John Allison Library to reproduce copies of this Doctor of Ministry project and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only.

The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the project, and except as hereinfore provided neither the project nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatever without the author’s prior written permission.

____________________________

#1008- 555 West 28th Street

North Vancouver, BC, Canada

V7N 2J7

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks are due to my faithful wife Janice and my three adult sons who believe in my calling and regularly encourage me in season and out of season. I am also appreciative for the support of my parents who believe in what I have been investing in.

Paddy Ducklow, my doctoral advisor, and the Carey Theological College Professors have been a great inspiration to me in my growing in action / reflection.

I would like to acknowledge the assistance and encouragement that I received from Haupi Tombing, a fellow pilgrim and Carey doctoral student who helped me stay focused.

Ron Richardson, Randy Frost, Roberta Gilbert, and Peter Steinke all gave me helpful advice as I have been expanding my understanding of Family Systems Theory.

I am grateful for our St. Simon’s North Vancouver congregation who have been the crucible of all that I have been learning. Our Bishop Silas Ng and our Anglican Mission Canada National Leadership Co-ordinator, Peter Klenner, have been strong supporters of this doctoral work when I have most needed it.

For the five North Shore couples who participated in the Strengthening Marriage workshop, I am deeply appreciative of your assistance.

I give thanks to our Lord Jesus Christ for his covenantal faithfulness to me through good times and challenging times.

ABSTRACT

How bridging emotional cutoff can strengthen marriages was the focus of this Doctoral Thesis Project. A four-evening workshop over one month on Strengthening Marriages was conducted with five currently married couples who had been previously divorced. The method for evaluating potential marriage strengthening and bridging cutoff was done through a qualitative interview conducted in person with each couple first before and then after the four-session workshop. A newly-developed Strengthening Marriage manual for the four- session workshop was produced which is transferable to other church and non-church contexts. Participants indicated that the workshop strengthened their marriage and reduced emotional cutoff through ‘fresh thoughts’ (43%) and conflict appreciation (19%). This research finding connects with the Family Systems Theory emphasis on clear original thinking and facing conflict as ways of strengthening marriages and bridging cutoff. There was also self-reported growth in the area of self-differentiation (11%) and marital learning (20%). This qualitative research on strengthening marriages adds to a growing body of research-based analysis, showing the benefits of Family Systems Theory. Bridging emotional cutoff through a covenantal approach is explored with particular reference to Ephesians 5 and Colossians 3.

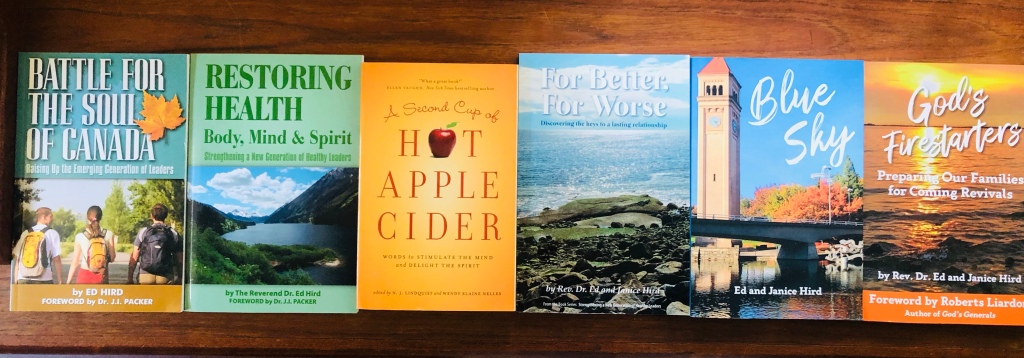

-Click to check out our newest marriage book For Better For Worse: discovering the keys to a lasting relationship on Amazon. It is an adaptation of the doctoral thesis. You can even read the first two chapters for free to see if the book speaks to you.

-Click to check out our newest marriage book For Better For Worse: discovering the keys to a lasting relationship on Amazon. It is an adaptation of the doctoral thesis. You can even read the first two chapters for free to see if the book speaks to you.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1) EMOTIONAL CUTOFF AND STRENGTHENING MARRIAGE

Introduction p. 1

a) Emotional Cutoff and Differentiation p. 18

b) Emotional Cutoff and Multi-generational Transmission p. 22

c) Bridging Emotional Cutoff p. 24

d) Emotional Cutoff and Coaching p. 29

e) Emotional Cutoff and Symptoms p. 31

f) Emotional Cutoff and Observational Blindness p. 35

g) Emotional Cutoff and Emotional Reactivity p. 38

h) Emotional Cutoff and Process Questions p. 41

i) Emotional Cutoff and Over / Under Functioning p. 45

j) Emotional Cutoff and Divorce p. 48

k) Emotionally Focused Therapy’s Approach to Attachment and Emotional Cutoff p. 53

l) Family Systems Theory’s Approach to Attachment and Emotional Cutoff p. 55

2) METHODOLOGY p. 57

3) FINDINGS p. 62

a) Bar Graphs p. 64

b) Pie Charts p. 73

4) STRENGTHENING MARRIAGE FROM A FAMILY SYSTEMS THEORY PERSPECTIVE

ai) Nuclear Family Emotional System and Strengthening Marriages p. 84

aii) Anxiety and Strengthening Marriage p. 91

b) Differentiation of Self and Strengthening Marriages p. 98

c) Triangles and Strengthening Marriages p.109

d) Family Projection Process and Strengthening Marriages p. 117

e) Family of Origin and Strengthening Marriages p. 119

f) Societal Emotional Process and Strengthening Marriages p. 125

5) THEOLOGICAL AND BIBLICAL INTEGRATION OF MARRIAGE STRENGTHENING WITH FAMILY SYSTEMS THEORY

a)Covenant-making God p. 130

b) Covenant-keeping in the midst of covenant-breaking p. 134

c) Covenant Marriage, Covenant Community p. 139

d) Love and Commitment in Covenant Marriage p. 142

e) Covenantal Marriage in Ephesians 5 p. 150

f) Covenant Marriage in Colossians 3 p. 163

g) Covenantal Differentiation in Marriage p. 167

h) Covenant-breaking, Marital Cutoff, and Remarriage p. 169

6) CONCLUSION p. 178

BIBLIOGRAPHY p. 187

APPENDICES:

i) Letter of informed consent p. 203

ii) Newspaper advertisement for the workshop p. 204

iii) Poster for the workshop p. 205

iv) North Shore Outlook article on the workshop p. 206

v) Interview questions p. 210

vi) Strengthening Marriage Manual p. 212

vii)Interview with Randy Frost about Murray Bowen p. 226

viii) Analysis of the Interviews with the Strengthening Marriage Workshop Couples p. 231

ix) New Features in the Post-interview research data p. 274

x) Glossary of Terms used in Family Systems Theory p. 289

xi) Marital Statistics for the North Shore and for BC p. 294

1) INTRODUCTION

Strengthening marriages through bridging cutoff has potential to bring benefit to marital life. A Family Systems Theory approach to strengthening marriage may reduce emotional cutoff through discovering strengths, honouring differences, appreciating conflict, and balancing closeness with personal space.

This Doctoral Thesis project is focused on strengthening marriages by bridging emotional cutoff. The concern is that in divorce and remarriage, people may be set up for further emotional cutoff, resulting in marital instability. Family Systems Theory holds that emotional cutoff increases future marital instability. The thesis is about the area of strengthening marriages because of the suffering and devastation on the North Shore of Vancouver when marriages disintegrate and cut off. While the North Shore represents three cities of West Vancouver, North Vancouver City, and North Vancouver District, there is a strong geographic, historic, and cultural alignment, heightened by our being separated from the rest of Greater Vancouver by the Burrard Inlet. The North Shore population is a transient culture that often increases instability to marriage. Marital pain is a deep pain that potentially affects everyone in the family emotional system. The goal of the Doctoral Thesis Project is to enable pastors and congregations to come along side people who quest for more stable and satisfying marriages. Marriage ministry is a normal part of Church life. Marriage Preparation, conducting weddings, and strengthening marriages is both part of our Church’s heritage and our Church’s future. Birth, marriage and death are three key transitions in life for which the Church historically has developed rituals. Weddings are times of significant life change in which clergy and the Church can be pastorally supportive. The hope is that other clergy may be able to make use of this material in pastoral coaching of married couples and those considering marriage in their congregations and community. Through strengthening marriages, genuine hope is given to a new generation that faith and God’s covenant community can make a difference in their relationships.

The covenant of marriage is God’s own idea. God, as a covenant-maker, is passionate about strengthening the marriage covenant. While covenant-breaking increases marital cutoff, covenant strengthening reduces marital cutoff. God has for many years gifted our North Shore congregation in helping struggling marriages, often seeing them strengthened and restored. Taking time to strengthen marriages is good marital stewardship. Marriages are worth investing in with the best that we can offer of our time, talent and treasure. Because there is no quick fix, strengthening marriages is both costly and messy. Strengthened marriages can help strengthen families, church and society. St Simon’s heart for emotionally cutoff marriages comes out of our own brokenness as a church. The St. Simon’s Church family has seen much emotional cutoff over the years in our marriages. God in the last number of years has been healing us and releasing a fresh conviction that in the words of Genesis 50:20, what was meant for evil, God has meant for good. This great marital pain has not been wasted. In standing with the emotionally cutoff and covenantally-broken, there has been a rediscovery that God is good, faithful and kind. God, as covenant-maker, rescues, renews, forgives and heals, taking what is broken and making it whole. God is for the emotionally cutoff and the covenantally-broken, and not against them.

The ministry problem is an examination of the emotional cutoff of marriages on the North Shore of Vancouver. The interest in strengthening marriages began with observing declining marriages on the North Shore among both Christian and other couples. A number of the St. Simon’s elders are people from divorced, remarried, and blended family backgrounds. Some of these have gone through marriage crises, then did Christian-based marriage counseling which aided in the restoration of their first or second marriage, and later became church leaders. This has given hope to other struggling marriages. It seems like someone has to go first in working on their marriage, in order to give courage to other struggling couples. People often tragically hold back from getting marital help out of shame or fear. Strengthened marriages can give hope to the emerging generation, some of whom are ambivalent about even becoming married. Their parent’s emotional cutoff and divorce are often mentioned as part of their marital hesitation. Marriage seems so uncertain and painful to them. Numerous North Shore couples are high-functioning or over-functioning at work, but are far less functional in their marriages, often resulting in emotional cutoff. The very skills that make a successful entrepreneur often backfire in the bedroom and the living room, with such people being “totally lost when dealing with intimate relationships.” Bowen commented:

In another group, a section of the intellect functions well on impersonal subjects; they can be brilliant academically, while their emotionally-directed personal lives are chaotic.[1]

There are a number of counseling agencies and practitioners on the North Shore. Some have been impacted through the Living Systems Centre (formerly called the North Shore Counseling Centre) involving Ron Richardson’s pioneering work in Family Systems Theory. Also involved in marriage-related family crises on the North Shore are police, courts, schools, North Shore Family Services, and social services. The churches on the North Shore conduct weddings and marriage preparation. The stand for ‘traditional’ marriage’ by St. Simon’s North Vancouver Church, in the midst of the historic Anglican realignment, has given the St. Simon’s congregation a visible platform and presence regarding strengthening marriages. As the Communications Officer for the new Anglican movement, there have been many opportunities to reflect on TV, radio and newspaper on the meaning of marriage. St. Simon’s North Vancouver has developed a reputation of being a place where many marriages have been restored over the years. Despite the high profile instability and cutoff of many current marriages, studies indicate that marriage can bring greater overall health than its relational alternatives:

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) reviewed health data gathered from more than 127,000 adults from 1999 to 2002. Regardless of age, sex, race, education, income, or nationality, married adults were least likely to be in poor health, suffer serious psychological distress and smoke or drink heavily.[2]

Over the years, there has been the opportunity to write many marriage-related articles in the North Shore Newspapers. For 25 years in the Deep Cove Crier, there has been a monthly column to an audience of 34,000 people, and also for ten years in the North Shore News from the year 2,000 to 2010. North Shore friends and readership have given much feedback about the importance of strengthening North Shore marriages. When told that the doctoral thesis project was about strengthening marriage, they universally said that this is what the North Shore Church and pastors should be investing in.

Murray Bowen, the founder of Family Systems Theory, called emotional cutoff the “process of separation, isolation, withdrawal, running away, or denying the importance of the parental family”. He is widely recognized even by his critics as one of the key founders of the field of Marriage and Family Therapy. In 1975, the emotional cutoff concept was added by Bowen as the second last of the eight Family Systems Theory concepts. The emotional cutoff concept was created by Bowen in order to “include details not stated elsewhere, and to have a separate concept for emotional process between the generations.” Until then, emotional cutoff was seen by Bowen as a “poorly defined extension” of the concepts of the triangle and multigenerational emotional process.[3] Bowen’s integrative creativity kept unfolding during the decades of his systemic theorizing. In adding his ‘Emotional Cutoff’ concept, Bowen convergently finished well. His coining of the emotional cutoff concept is an example of how Bowen was able to see the invisible systemic connections that most of us miss. The more we understand emotional cutoff, the greater opportunity we have to strengthen marriages in our congregations and communities.

The backdrop for Bowen’s concept of emotional cutoff was the many young people running away from home during the 1960s. Parents were seen as the identified problem and getting away as the quick-fix solution. Emotional cutoff however unexpectedly brought the unresolved attachment issues with them to their new settings.[4] Bowen’s assessment of the Hippie movement’s emotional cutoff from their parents rings true. It may have looked to Hippies as if they were being themselves and differentiating. More often they were being their pseudo-selves rather than their core selves. Their pseudo-selves were emotionally fused to their parent’s pseudo-selves; the result was emotional cutoff. The term ‘emotional cutoff’ was chosen almost reluctantly by Bowen after much reflection.[5]

There is disagreement about the theoretical parameters of the term ‘emotional cutoff’. Does emotional cutoff only or rather primarily refer to one’s relationship with one’s parents? Cutoffs are either 1) primary when directly related to one’s parents, or 2) secondary, indirect, and inherited when based on interlocking triangles and on the multigenerational emotional process, which can be traced back to the primary parental cutoff. In light of Bowen’s use of the phrase “separation of people from each other” to describe cutoff, the term ‘cutoff’ can also be applied to secondary relationships, rather than just the parent-child relationship. Emotional cutoff therefore is more systemic and multi-layered than just hierarchical. Parental cutoff in one’s past shapes the degree and intensity of one’s emotional cutoff in present and future relationships.[6]

Family Systems theory brings potential paradigm shifts in which we see previously invisible emotional systems. Rather than speak of mental or psychological illness, Bowen used the term ‘emotional illness’. Bowen defined the term ‘emotional’ to mean ‘instinctual’. Steinke said:

Emotionality signifies what is instinctual in human behaviour, what is imprinted in our nerves as innate, and what embraces the deep biological commands on how to live. (Bowen) was not alluding to feelings – love, hate or anger. ….Instincts are quick, sudden, and immediate…[7]

If one does not understand how Bowen defines emotion, the rest of Family Systems Theory will make much less sense. The term ‘instinctual’ is used by Bowen exactly as it is in biology, rather than in the restricted psychoanalytic sense. In choosing not to define emotion as equivalent to feeling, Bowen admitted that his definition is a minority opinion: “Now most people in the world use emotion as synonymous with feeling. I’ve never done that.”[8]

Titelman elaborated on Bowen’s definition of emotion, saying that it denotes that the family is a system that automatically –below the level of feeling – responds to changes in ‘togetherness’ and ‘individuality’ within and among the membership of the extended family.[9] The emotional / instinctual is a reaction to systemic imbalance between marital closeness and personal space. Enabling this systemic balance through bridging cutoff was the focus of Session #4 of the Strengthening Marriage workshop. Many practitioners from other theoretical frameworks critique Bowen Theory with little awareness that Bowen was talking about instincts in this context, not feelings. Unless people understand this key definition, they will just be talking past each other. Emotional cutoff is not identical to feeling cutoff. Reducing the systemic dominance of the instinctual is at the heart of bridging cutoff.

When people cannot remember when and why their ancestors left another country, it is often a clue to emotional cutoff. Emotional cutoff is the extreme form of unresolved emotional distance. Titelman observes that “the emotionally distancing behavioral patterns of cutoff…includ(e) emotional isolation, withdrawal, flight, collapse, and geographic distancing…”[10] The mechanisms for the cutoff process are internal emotional distancing, or a combination of internal and physical emotional distancing. Because cutoff is a matter of degrees, it is often challenging to determine exactly where distance ends and cutoff begins.[11] The degree of cutoff is a combination of the amount of distancing and the current level of anxiety in the relationship. Emotional distance is an instinctual flight reaction from emotional intensity. Without chronic anxiety, emotional distance often does not morph into emotional cutoff. Anxious distance between generations is at the heart of emotional cutoff. Through such distance, emotional cutoff is able to regulate the emotional fusion that often occurs in multi-generational transmission.[12]

The phenomenon of cutoff is not to be judged negatively by the pastoral coach or the married couple as “a pathological relationship process”, but rather is analyzed neutrally to understand its function in the family emotional system. Dropping value judgments helps us observe the systemic functionality of emotional cutoff. This Bowenian neutrality brings to mind Jesus’ insight in Matthew 7:1 about not judging lest one be judged. Premature judgment reduces our ability to see and analyze cutoff. Distance and cutoff are not so much spatial as relational and ethical. Infrequency of contact is one of our most objective clues in assessing the existence of emotional cutoff.[13]

Shann Ferch and Dawn McComb described cutoff, overcloseness (fusion), silence or anger towards parental figures as typical relational responses to generational wounds. A wound is an indication that something has been systemically pierced, cut, or broken.[14] The more wounded we are generationally, the more likely that distance will turn into emotional cutoff. Such cutoff is connected with relationship dissatisfaction:

Both emotional reactivity and emotional cutoff (indices of affect regulation), for example, have been linked to decreased relationship satisfaction (Skowron, 2000; Skowron & Friedlander, 1998) and increased symptoms of negative mood (Skowron & Friedlander, 1998) in adult populations.[15]

Cutoff is sometimes a response to nodal events that bring shock waves spanning several generations. Bowen defined nodal events or nodal points as referring to the intersection of the onset of symptoms in the child with dates of nodal events in the parental relationships. Extreme nodal events include disease, unemployment, emigration and death. The lower the differentiation, the more frequent and intense will be the shock wave nodal events.[16] The MESI Question #3 “What stands out for you in your marriage as its most important turning points / times of change?” was specifically designed to help the five couples to look at nodal events and resulting emotional cutoff in their marriages.

Emotional cutoff has been linked to violence. Where there has been generational violence, cutoff functions to increase its replication in the present generation. When cutoff resulting from family violence is not addressed, it may end up fostering the very violence that it is seeking to escape from. Walker’s research with 290 people in treatment centres showed that those reporting greater cutoff are more likely to report at least one instance of relational violence in the past year.[17]

Past fusion become future fusion through the generation mechanism of emotional cutoff. Sadly our running from fusion through distance and emotional cutoff reproduces the very thing that we are anxiously seeking to avoid. Just as separation is overwhelming to the emotionally fused, intimacy is threatening to the emotionally cutoff. Given their fear of closeness, they neither want to be smothered nor abandoned.[18] The interlocking process of stuck-together fusion and emotional cutoff expresses the two faces of undifferentiation. Marital cutoff is the flip-side of fusion.[19]

An imbalance of marital closeness and personal space elicits either cutoff or fusion. Both cutoff and fusion are at the extreme ends of the closeness – personal space continuum. While fusion is separation-anxiety, cutoff is closeness-anxiety. Hollywood movies often flip back between fused closeness and emotionally cut-off distance. Symbiotic fusion is vividly expressed in the paradoxical claim: “I can’t live with you – I can’t live without you.” Without emotional closeness, marriages are left with a marked emotional distance which Bowen called emotional divorce.[20] Session #4 of the Strengthening Marriage Workshop looked extensively at this area, particularly in balancing closeness and personal space.

Healthy boundaries reduce one’s multigenerational default to distance and marital cutoff. Better marital boundaries allow people to connect with their spouse openly, equally, and with self-definition. Through boundaries, spouses are able to stay in touch when tempted to distance. The healthiest marital boundaries are secure but permeable, allowing spouses to think, feel and act for themselves.[21] In Session #3, the five couples were taught that learning to say no and to set healthy boundaries strengthens marital intimacy and reduces emotional cutoff. Both pursuing and avoiding one’s spouse is counterproductive. Sometimes what feels like a lack of connection is actually evidence of too much reactive marital fusion. Depressed spouses are sometimes reactively cutting off from marital fusion. The goal in strengthening marriages is to increase unfused connection which balances closeness and personal space.[22]

Married couples often suffer from a repeating pattern of too much closeness and too much distance. Bowen called it a “closeness –fighting- rejecting cycle.” Feeling crowded can be just as painful as feeling abandoned. Being close can be very demanding. Distance is often vital in preserving the pseudo-self.[23] Kerr and Bowen vividly commented that

a hallmark of a conflictual marriage is that husband and wife are angry and dissatisfied with one another…Their relationship is like an exhausting, draining, and strangely invigorating roller coaster ride; people threaten never to buy another ticket, but they usually do…[24]

Even when distant, conflicted couples are usually focusing mostly on each other. Distancing spouses often take refuge in overwork, substance abuse, or jobs requiring travel. Sometimes one spouse distances from the other by anxiously focusing on their child. An over-focus on the family and children is often a marital conflict avoidance mechanism. Ferrera holds that “divorcing partners who have been child-focused in marriage will most likely be child-focused in divorce.”[25]

Because of the lack of an adaptive role, conflicted couples often have the most overtly intense of all relationships. The loss of flexibility or emotional reserve causes the marriage relationship to become an emotional cocoon. With conflicted couples, the intensity of the anger and negative feeling in the conflict is as intense as the positive feeling. Bowen described the common syndrome of ‘too much closeness’ as ‘weekend neurosis’ or ‘cabin fever’.[26] Emotional cocooning and cabin fever set the stage for marital cutoff as the ‘solution’.

To reduce symptoms in a married couple, balance is essential, as too little or too much distance creates anxiety. Symptoms and human problems erupt when the relationship system is unbalanced. Any lack of balance in a marital or family-like system can create a sense of threat. Some have even suggested that systemic balance should be included as a future Bowenian concept. Unless the distance is right, married couples cannot hear each other. The right amount of emotional space increases accurate marital hearing.[27] Unbalanced distance can lead to polarization and even emotional cutoff. Systemic unawareness increases marital polarization. The more cutoff we are, the more blind we become to our polarized relationship. Polarization easily happens when married couples are convinced that an issue must be immediately resolved. Winning the marital battle becomes everything, as sadly illustrated in the tragic movie War of the Roses.[28] Polarization is marital homeostasis, pretending to be a morphogenic revolution. Bowen said that marital polarization increase symptoms and prevents change:

…for some reason the human brain is open to polarities – to opposing viewpoints. And the human struggle wants to argue these viewpoints…So the human being is set up for arguing polarities. There is a never ending supply of polarities.[29]

Emotional cutoff is the mechanism for managing anxiety related to the connection with one’s original family. The emotional anxiety and loss of self connected with fusion results in some married couples wanting to run away, to distance, to cut off. Emotional fusion is inherently painful, and increases our alienation from others, including our spouse.[30] Generation gaps are fusion-based family cutoffs.

Watching functioning is key to family systems breakthroughs. The more thorough our understanding of human functioning, family functioning and self-functioning, the greater is our opportunity for morphogenic change and reducing cutoff. Fusion and cutoff are two key temptations in human functioning, which include the pulls to dominance, dissolving, or absence. Cutoff is often a way of overfunctioning in an attempt to achieve self-sufficiency. The anonymous voices of 1 Corinthians 12 which say ‘I don’t need you and I don’t belong’ represent self-sufficient, overfunctioning cutoff. This helps explain how some people do exceptionally well after generational cutoff, only to have their next generation flounder and underfunction due to fewer relationship resources.[31] Overfunctioning will often triangle the next generation into underfunctioning.

Fusion can evolve into cutoff, which inevitably evolves back into fusion. Cutoff has been linked in several studies to marital discord and long-term marital dysfunction. Michele Denise Akers-Woody commented that “emotional cutoff has been found to predict marital discord and may harm the marriage in the longterm.”[32] Cutoff can take many forms with married couples, such as physical distance, or avoidance of emotionally charged subjects. Often those who were overly fused in their childhood are most prone to emotional cutoff in marriage. Cutoff is frequently a matter of trading one highly fused rigid triangle for another highly fused rigid triangle which has no room for the former triangle.[33]

Distance and fusion play off of each other. The most universal mechanism for dealing with marital fusion is emotional distance from each other. This method is found in a high percentage of marriages to a major degree. Bowen admitted that he unsuccessfully used distance, time, and silence to cover up his emotional fusion. Contemporary Bowen therapists are paying more attention to gender issues. Ora Peleg and Meital Yitzak uncovered gender differences in married couples coping with fusion and separation anxiety:

A significant relationship was found among men between fusion with others and separation anxiety: a high level of fusion was found to correlate with a high level of anxiety. Among women, a high level of emotional reactivity was related to a high level of separation anxiety.[34]

Emotional fusion initially relieves anxiety for the married couple; then it increases anxiety because of the loss of self which then in turn causes one spouse to use distance as an anxiety-reducer. While distance temporarily reduces anxiety, it then brings anxiety-inducing loneliness. Indications of transmissible multigenerational marital anxiety are marital instability, separation, divorce and never marrying. Michael Kerr and Murray Bowen described the two fusion/cutoff polarities as crowdedness and loneliness. ‘Heavy’ fused environments are more challenging than ‘light’ environments.[35] The basic problem in families may not be to maintain relationships but to maintain the self that permits non-disintegrative relationships. Anxiety pops up with every dysfunctional response. Only healthy, calm, unfused connecting brings lasting reduction of anxiety and emotional cutoff. Individuals who are cut off from their families generally do not heal until they have been reconnected.[36]

What married couples are avoiding with emotional distance is their own fused reactivity to each other. Resentful badgering over the distance only increases the lonely distance. Distance serves as an emotional insulation.[37] Hiding and distance is found in both compliant and conflictual marriages. Emotional distance is a high price for tense peace. A lot of marital conflict is ironically fostered by attempts to avoid marital conflict. Bowen noted three functional ‘benefits’ of marital conflict which included emotional connection, guilt-free distance, and someone on which to project our anxiety.[38]

The greater the reactive fusion is, the greater the intensity of the marital problems. Bowen believed that fusion was strongest in the ‘togetherness’ model of marriage, a fusion that is at the core of much marital disruption. With fusion, we give away power to our spouse and end up seeking permission from them just to be our self. Giving away power is giving away self. One of the unintended consequences of emotional cutoff is increased loss of self. Giving up self is the embracing of non-existence for the sake of an unhealthy family system. To give up the core, genuine self is to cease to be, to fully live. When cut offs occur, the person always loses something of himself or herself. In Session #1, the five couples were taught that overcoming a loss of self brings energy and joy to one’s marriage, reducing emotional cutoff. To appropriate the power of Easter for our marriages, we need to baptismally die to the pseudo-self, the old nature, the flesh/sarx, and rise to our new genuine self in Christ.[39]

1a) Emotional Cutoff and Differentiation

Cutoff is not differentiation. Rather actual differentiation is the antidote to emotional cutoff. High differentation and low emotional cutoff are linked with marital satisfaction by Skowron’s study of 118 couples, Peleg’s study of 121 men and women, and Miller’s study of 60 couples. Differentiation is the core process in the family emotional system. There are at least four factors that influence one’s level of differentiation. These factors include emotional cutoff, reactivity, fusion and taking ‘I’ positions. At the heart of differentiation is the balancing of intrapersonal and interpersonal dimensions of our humanity. Intrapersonal balance or self-differentiation enables a person to distinguish between one’s thinking and feelings. Interpersonal balance or family differentiation brings synchronicity between closeness and personal space.[40] While differentiation is a theoretical concept, empirical studies are beginning to confirm its accuracy. Peleg and Arnon noted:

Higher levels of differentiation (i.e., less emotional reactivity, emotional cutoff and fusion, and

more I-position) have predicted higher levels of psychological maturity and marital satisfaction

(Peleg 2008; Skowron and Friedlander 1998; Tuason and Friedlander 2000) and more positive

overall alliances (Lambert and Friedlander 2008), whereas lower levels of differentiation have

been linked to psychological distress, higher levels of trait anxiety (Skowron and Friedlander

1998), stress (Skowron et al. 2009), physiological symptoms (Skowron 2000), and social anxiety

(Peleg 2002; 2005).

Differentiation is sometimes confused with distance. Some people anxiously use distance and cutoff to simulate self-differentation by looking independent.[41] Bowen said that coaching aims to convert the cutoff into an orderly differentiation of a self from the extended family. Cutoff is standing out against others whereas differentiation is standing out from others. Standing out against others brings rigidity and distracts people from doing their own marital and self work. Steinke observed that “to continue the position of ‘againstness’, the emotional distancer often becomes dogmatic, opinionated, and doctrinaire.”[42] The less differentiated the spouse is, the more they will be blaming and prone to cutting off the other spouse. At the highest level of differentiation, we grow away from our parents; at the middle level we tear away; and at the lowest level, we cut away, cutting off and even collapsing. The first step in differentiation is when one spouse starts taking responsibility for self and reduces the blaming of their marital partner.[43] The five couples were taught in Session # 2 that working on one’s own self is the key to raising the level of differentiation in the marriage, thereby bridging cutoff.

Cutoff paradoxically reflects a problem, ‘solves’ a problem and creates a problem in terms of reducing and increasing anxiety. Running away from anxiety is impossible, because it is chained like a ball (or a pet rock) to our ankle. It always comes along for the ride. The anxiety of life, as with Jonah’s whale, has a way of chasing us until we stop running from who we are and are called to be.[44]

One cannot cut one’s self off from multigenerational anxiety, but rather only from the knowledge of the sources of this anxiety. Such cutoff causes anxious people to ‘fly blind’ relationally without any generational, emotional map. The loss of multigenerational connection through undifferentiated cutoff produces an unhealthy excessive dependence on the present generation. Overdependence raises our anxiety level, making us more likely to cut off our spouse. Cutoff causes us to minimize our past and exaggerate our present.[45] This is too great of an emotional load for one generation to bear alone. The present marital moment was never meant to be the full weight of life in isolation. Putting the full weight on the present marital moment is like driving a three-ton tractor onto a frozen Canadian lake intended only for amateur hockey. Multigenerational connectedness is the healthy marital alternative to multigenerational fusion or cutoff. In Session #2, the five couples were taught that the high road to marital growth and bridging cutoff is through a deeper understanding of the family we were raised in.

Self-differentiation honours differences and otherness. Homeostatic fusion demands sameness. Cutoff is pseudo-separation. Fusion, rooted in unresolved emotional attachment, often presents itself in the guise of cutoff. Marital and family cutoff can be subtle or more dramatic. The compliant non-present spouse may simultaneously pretend through his / her pseudo-self to be present. The pseudo-self is an actor, a pretender, and an imposter. For this reason, the pseudo-self can be very persuasive in its acting as if it is engaged and maritally connected. That is why husbands have sometimes said that they didn’t know that there was any marital problems until the moving truck arrived. Both those cutting off and those being cutoff feel powerless. They mistakenly think that the other spouse has the power. Their cutting-off is often a reaction to their own perceived marital powerlessness. When spouses insist on their own way, marriage becomes a dreadful place of vying for power.[46] We should never underestimate our capacity to embrace the darkness of revenge with those whom we have loved and are still fused.

The lower the level of differentiation in married couples, the more they will use cutoff to reduce the anxious symptoms of emotional fusion. Cutoffs are liable to occur when the conforming demand overwhelms the drive for differentiation. Our people-pleasing and conflict avoidance can drive us to cutoff places that we never intended to go. With cutoff, we lose the opportunity to face, to process, and to grow through our conflicts and differences inherent to marital relations. At the lowest level of differentiation, cutting off results in emotional collapse, accompanied by internal cutoff as a way of denying the ongoing parent-child attachment.[47] Low differentiation increases martial cutoff.

1b) Emotional Cutoff and Multi-generational Transmission

Ignorance is not bliss. The more cutoff, the less the awareness there is of one’s multigenerational reactivity. We lose both the facts and the emotional patterns. Cutoff increases reactivity. The more cutoff, the more reactivity.[48] Two sure signs of emotional cutoff are denial of the importance of the family and an exaggerated façade of independence.[49] Rosemary Lambie and Debbie Daniel-Mohring commented:

Choosing friends of which parents disapprove (as adolescents), getting in trouble with the law, and abusing substances are way adolescents try to cut off from parents. This declaration of independence from family is not the same as differentiation of self. It in no way resolves the emotional fusion with the parent.

Like with many teenagers, emotional cutoff is about “acting and pretending to be more independent than one is”. Both pretending and exposing our pretending is a significant Bowenian theme. One of the greatest problems with multigenerational cutoff is that it impedes healing until unfused reconnection occurs. Cutoff creates emotional stuckness, solidification, and stagnation.[50]

Without nonfused extended-family support, there will continue to be increased marital instability and cutoff in this present generation. Reduced marital reproduction has been linked with emotional cutoff and the absence of extended-family support. With the decrease in social complexity that accompanies emotional cutoff, there is a generational loss of flexibility and diversity in our marriages. With multigenerational cutoff, the person perceives that there are fewer choices in their marriage. Emotional cutoff reduces the social complexity and increases systemic rigidity in marriages. Sometimes covert marital cutoff is hidden behind a cozy togetherness which masks an internal cutoff.[51] Cutoff thinking is more rigid, narrow and polarized, with differences and personal issues being avoided.

Kerr and Roberts have experimentally explored and demonstrated the link between cutoff, poor functioning, and greater marital conflict:

This finding supports Bowen’s theory that individuals who are emotionally cutoff are less well adjusted in their marital relationships and are lower functioning as illustrated by their lower scores on the marital communication directory.[52]

Abby Adorney’s research confirmed the Family Systems Theory hypothesis that emotional cutoff measurably impacts marital functioning. Cutoff is also closely related to the level of gossip and evasiveness. When we elusively avoid the discussion of certain family of origin issues, we maintain marital toxicity.[53]

1c) Bridging Emotional Cutoff

Can emotional cutoff be bridged? Facing our own multigenerational marital cutoff can be a daunting prospect. It is encouraging to know that cutoff is not an emotional death sentence that we are fatalistically doomed to endure. As Christ-followers with a strong theology of hope, this is good news. Richardson wrote that emotional cutoff can be reversed through 1) bridging cutoff, 2) gaining knowledge about the functional facts in the emotional system of our family and our part in it and 3) then managing self in the midst of having close contact with members of the system. Rigorous self-examination and family evaluation are vital in reversing cutoff. In order to bridge emotional cutoff, one must define self through 1) working toward person-to-person relationships, (2) becoming a better observer and managing one’s own emotional reactiveness; and (3) detriangling self in emotional situations.[54]

Neutrality and curiosity reduces cutoff. The greater the multigenerational marital cutoff, the more challenging it is to integrate Bowen theory. Anxiety may reduce the couple’s desire and ability to learn. Simultaneously those who are most maritally cutoff may be the most motivated to learn Bowen theory.[55] Being emotionally cutoff can cut either way: either making couples more defensive or more desperate for a better way. Bowen made use of parables and displacement stories about parallel couples as a way of indirectly teaching highly anxious couples. Bridging cutoff requires recognition of the existing marital fusion. It is often difficult to recognize emotional fusion because it feels so normal. It may be all that we know. A first step in bridging cutoff might be to name our blindness about how maritally fused we probably are. When we first attempt to bridge multigenerational cutoff, some may see us as betraying our family homeostasis and going over to the enemy. Naively attempting to bridge cutoff without a clear family systems understanding can bring more distance and tension in the marriage and family relationships. If we rush in looking for a quick fix, we just make multigenerational cutoff worse.[56] In Session #3, the five couples were taught that marital conflict is best resolved when we say no to quick fixes and take the long-term perspective.

The goal in bridging marital cutoff is to replace fusion and reactive distance with “a reasonable degree of separateness with contact”. Reducing both emotional cutoff and fusion requires that marital closeness needs to be a choice rather than a pressurized obligation. Playfulness and appropriate humour help us become close while simultaneously reducing marital cutoff. As our marriages become more goal-oriented and future-focused, both closeness and bridging of cutoff become more possible. Self-reflective detachment enables us to gradually bridge the emotional gap. It is challenging to bridge cutoff and enhance closeness without giving up on self.

Bridging marital cutoff changes the adaptability of the brain and physiology of the bridging individual. As part of bridging cutoff, one can bring greater flexibility through increasing self and other-awareness, examining one’s mindset, reducing immature expectations and blaming, and generating options for alternative responses. Rather than being a quick fix, bridging multigenerational cutoff through Bowen Theory is a long process that needs to be worked on throughout one’s marriage and life. We will never outgrow the need to keep on restoring these multigenerational bridges. Viable contact with the past and present generations, both living and deceased, brings higher functioning.[57] Calm multigenerational contact helps bridge and reverses the patterns of avoidance, blame, withdrawal and cutoff. Thoughtful observing and controlling of one’s reactivity reduces the generational tendency to cut off through withdrawal. Multigenerational dialogue brings cleansing from cutoff, fusion, rigidity and emptiness. Because cutoff instinctively shrinks our definition about who is included as family, it is best when bridging cutoff to contact all family members rather than a narrow subset.[58] Whoever is excluded from the family becomes a marker, pointing to traumatic cutoff. Emotional cutoff solves nothing.

From a Family Systems Theory perspective, emotional detachment rather than emotional cutoff is the effective way to reduce emotional attachment or fusion. To detach is to be freed from unbalanced attachment that lacks individuation and personal space. Unresolved attachment reflects our lack of core self. Our unresolved attachments are usually parental, but affect every other relationship. The marital past remains the unresolved present until we bridge cutoff. Unresolved parental attachment is closely linked to numerous undesirable symptoms and problems. Bowen said that there are people who never separate from their parents and – all things being equal – will remain attached forever.[59] As Genesis 2:24 and Matthew 19:5 teach us, marital cleaving is dependent upon parental leaving.

The greater the unresolved attachment, the less one can be a self with one’s spouse and with one’s parents. Unresolved emotional attachment is linked with chronic anxiety.[60] The chronically anxious are highly vulnerable to both multigenerational cutoff and fusion. Unresolved emotional attachment is equivalent to the degree of undifferentiation in a person and in a family. No one becomes an adult without some unresolved emotional attachment.[61]

We are all an emotional work in progress. Unresolved emotional attachment defines the relationship between emotional and intellectual functioning, bringing a rigid, dependent fusion dominated by the automatic emotional system. The more rigid we are, the more vulnerable we are to loss of self and / or loss of our marriage. Defensive rigidity is emotional death, often resulting in marital death. Emotional cutoff is the universal mechanism for dealing with unresolved emotional attachment.[62] Bowen held that

One of the most important functional patterns in a family has to do with the intensity of the unresolved emotional attachment to parents, most frequently to the mother for both men and women, and the way the individual handles the attachment. All people have an emotional attachment to their parents that is more intense than most people permit themselves to believe.

The more we deny our unresolved emotional attachment, the greater the power of emotional cutoff in our marriages. The centrifugal intensity of cutoff using its emotional booster rocket to leave the earth’s atmosphere is connected to the gravitational intensity of fusion, trying to keep us on planet earth. The degree of emotional fusion is equal, primarily, to the degree of emotional attachment to one’s parents.[63]

1d) Emotional Cutoff and Coaching

Coaching reduces emotional cutoff and strengthens marriages. The Bowen model prefers the term ‘coaching’, shifting from couch to coach. Papero described the coach as more of a consultant and teacher than a therapist. As Bowen put it,

“Terms such as ‘supervisor’, ‘teacher’, and ‘coach’ are probably best in conveying the connotation of an active expert coaching both individual players and the team to the best of their abilities.[64]

Longevity rather than frequency of coaching is linked to impacting family of origin issues and reducing marital cutoff. The maturing of marriages and families is a natural biological process that takes time. It takes years to bring lasting systemic marital and family change. In western society, people often want fast results, including reducing emotional cutoff quickly through strengthening of marriages. Individuality is slow to emerge and easily suppressed underground. Bowen warned against the solution that becomes the problem.[65] Reducing cutoff through coaching doesn’t mean telling married couples what to do, but rather asking questions that help them understand their own emotional processes and how they function within them. Greater clarity is key. As pastoral coaches, we must resist the pressure to collude with the couple by finding answers for them. A basic premise of Bowen Theory is that marriages and families can find their own answers if they work on it. The pastoral coach, like a sports coach, may diagram the patterns or plays, and assists in developing a game plan or goal-oriented marital vision. But it is up to the couple to implement the marital game plan.[66]

The couple is encouraged in Bowen Theory to talk directly to the pastoral coach rather than to each other. Through externalizing the thinking of each spouse in the other spouse’s presence, emotional cutoff is reduced as marital curiosity increases. In coaching a couple, Bowen used to say: “Give me a few minutes of your most objective thinking.” Ideational thinking about our thinking is the Bowenian way forward: who has been thinking, how much he/she has thought, what were the patterns of the thoughts, and what kind of working conclusions came from the thinking.[67]

When the pastoral coach has mastered the family systems theory concept for his / her self, the orientation and very self of the coach communicates the transformative marital vision. Marital coaching is about focusing on the structure rather than the symptomatic ‘IP negative’ (Identified Person Negative). The coaching challenge is to defocus from the symptomatic focus, and refocus on the emotional field.[68] Most reduction of marital cutoff is intended to happen out in the field rather than in the pastoral coach’s office. The pastoral coach is a calming presence who reduces the tendency of the married couple to vent, dump on each other, and emotionally cutoff. A pastoral coach needs to believe one’s position enough to be calm for it. It is easy to regress while bridging cutoff without the encouragement of a coach. Pastoral coaching of married couples is vital for strengthening marriages and bridging cutoff, both on the North Shore and beyond.[69]

1e) Emotional Cutoff and Symptoms

Emotional cutoff produces noticeable marital symptoms. When coaching married couples, it is important to pay close attention to symptoms, not so much to relieve the symptoms, but rather to use the symptoms as “a pathway into the emotional system.”[70]

The Freudian model tends to see symptoms as indications of intrapsychic diseases within the patient. The Bowen model instead sees symptoms as indications of a wider emotional system that transcends the mere individual. Symptoms are multigenerational. The symptomatic spouse does not necessarily need to be the focus of pastoral coaching, as the aim is to modify the whole unit, acknowledging reciprocity between functions. Symptoms like marital distress usually develop during periods of heightened or prolonged family or group tension.[71] One of the major Family Systems Theory learnings has been to watch for how people catch and transmit their emotional flu symptoms within their family system triangles. Because symptoms are a product of triangulation, the symptoms themselves tell us who is absorbing anxious undifferentiation, and who is projecting this onto another member of the triangle. Sometimes when one spouse successfully sets boundaries, the other spouse will reactively develop physical symptoms. Thomas Murray, in a study of 201 patients with fibromyalgia, has significantly correlated higher levels of emotional cutoff with more severe fibromyalgia symptoms.[72]

Bridging cutoff is closely linked to lasting symptom reduction rather than the temporary symptomatic relief that comes with emotional cutoff.[73] Bowen said that maintaining and / or reestablishing viable emotional contact with one’s family of origin will make symptoms softer and more manageable. Quick symptomatic relief of anxiety is not the same as long-term marital change.[74] Some psychological researchers are primarily measuring symptomatic change rather than the more significant long-term systemic change. As such, the quantitative marital research results may be misleading. One of the signs of marital cutoff is strong homeostatic resistance to change. Even failed marital change has unexpected benefits. The good news is that by valuing and observing our initial failures to change, we are more likely to experience lasting marital change.[75] Friedman suggested that marriages should not be measured by longevity or happiness but rather by being symptom-free in three locations: 1) in the marital relationship (as conflict, distance or divorce), 2) in the health of one of the partners (physical or ‘mental’), or 3) in one of the children (though this last could also be placed in the space between the parent and the child).[76] Marital symptoms are intensified by emotional cutoff and reduced by family of origin work.

The presence of symptoms is linked with a lack of marital flexibility and an inability to recover from emotional arousal. The relationship between chronic anxiety and the resulting symptoms may vary significantly.[77] Kerr and Bowen viewed symptoms like over / under eating, over / under achieving, excessive alcohol / drug use, and affairs as indicators of having given up too much self, often absorbing anxiety within the marital relationship system. The symptomatic situation is sometimes seen as a ‘no exit’ position. Ironically, conflicted couples sometimes have fewer symptoms, because their conflict can provide a very strong sense of emotional contact with the other spouse.

Chronic symptoms are sometimes a diversion from the most challenging relationship problems of the couple and / or family. Facing one’s relational anxiety is often more threatening than addressing one’s relational symptoms. Many couples blame all their marriage problems on a lack of communication. While this claim makes common sense, it may be misdirected. Communication is less a problem than a symptom. The actual problem is the relationship position or posture itself. Predominant relationship patterns shape how one symptomatically expresses one’s anxiety. The symptom of marital conflict occurs when one spouse externalizes their anxiety onto the other spouse; in contrast if the predominant pattern fosters dysfunction, then high anxiety is characterized by symptoms in the spouse or child.[78]

Who is most vulnerable to developing symptoms? The compliant or adaptive spouse picks up the anxiety projected from the dominant spouse, becoming more anxiously at risk for a symptom. The dominant spouse engages in will conflict, trying to will another to adapt to them, resulting in a loss of self and an increase of symptoms like anorexia, suicide, schizophrenia, abuse, violence, and many chronic physical diseases.[79] Domineering attitudes, rather than fostering healthy marriages, encourage emotional cutoff. Domineering is not the way of the servant King.

Focusing on the symptoms of the married couple tends to obscure the strengths of the couple and increases emotional cutoff. Married couples often come for coaching with a sense of failure. By focusing on what is right with the couple rather than on their pathological symptoms, one decreases the anxious reactivity and cutoff of the couple. Focusing on strengths is rarer than one might expect.[80] Symptoms remind us that “the human power for preservation, healing and change are already resident in the (married couple).” The resources are already there in the emotional system of the couple. They just need to be discovered and tapped into. We can choose to step out of the anxious worry loop when major regressive symptoms are adding to the anxiety of the married couple’s emotional system.[81] When we choose to address our symptoms, we can pull out of the cutoff spiral. Symptoms need not have the last word in our marriages.

1f) Emotional Cutoff and Observational Blindness

Emotional cutoff is directly related to observational blindness. Reading the original works by Bowen removes much observational blindness about how marriages function. The more we nonjudgmentally observe, the less we maritally cutoff. Observational blindness is rooted in the difficulty of seeing things that do not fit one’s theoretical frame of reference. We underestimate how difficult it can be to perceive things that we do not want to see. Bowen held that one has to become an observer before it is possible to see. The less that we see, the more we disconnect. The more we see, the greater neutrality. Conversely the greater the neutrality, the more we see. The ideal neutrality, said Papero, is like quietly watching the ripples of a mountain pond. Kerr and Bowen commented that “the closer we get to ourselves, the greater the pressure to see what we want to see or, at least, to see what we have always seen.” Observing requires a robust self-regulation of one’s emotional reactivity.[82]

The five couples were taught in Session #2 that objectivity about one’s self and marriage increases marital satisfaction. Gilbert and Bowen described such observing as being like putting on a lab coat like a scientist or watching from a space craft. In Bowen’s 1959 Prospectus, he compared this to moving from a playing field to the top of a stadium to watch a football game.[83] This observational discipline could be compared to that of going to a gym over an extended period of time, pushing through discouragement while making use of a personal trainer. Learning to become an observational scientist is just as challenging. It takes time to retrain and develop those observational marital biceps. This is in fact a lifetime project till death does us part.

Objective marital change requires an objective change in how we observe our marriages. When we maintain objectivity, we are able to “think about subjectivity, feelings, and emotions without triggering more subjectivity, feelings, and emotions.” Through developing our observational biceps, we have feelings but they don’t have us. They don’t control our life decisions or define our core self. This is not about being a 21st Century unfeeling Dr. Spock of Star Trek fame. It is rather about being aware of our feelings, while choosing which feelings to act upon.[84] When coaching married couples, observational objectivity is vital as it helps protect us against fusion and compassionate collusion. Objectivity will be lost if we focus with couples on content issues like sex, money and children, especially on issues of right or wrong, fairness and rights. Note-taking helps us avoid taking marital sides.[85]

Reducing emotional cutoff through increasing one’s marital objectivity is very demanding. The greater our awareness of marital triangles, the more objective we will become. Bowen was convinced that the only person we can change is ourselves. Are we willing to own our part in the marital system? If a person can discover and correct the part that one plays, all the others will automatically correct their parts.[86] Owning our marital part is very challenging because we are often so remarkably homeostatic, blind and defensive. As Jeremiah 17:9 painfully reminds us, our hearts are deceitful above all things. Bowen taught that it is never really possible to change another person but it is possible to change the part that self plays.[87] Reducing marital cutoff requires a radically objective assessment of one’s self, not just one’s spouse.

Intentionality is key in bridging cutoff through observational objectivity. It is very easy to lose objectivity, either as a spouse or as the pastoral coach. Thoughtful assessment of the marital system increases objective effective treatment. To maintain objectivity, we must be careful what we promise as results.[88]

1g) Emotional Cutoff and Emotional Reactivity

The higher our emotional reactivity, the higher is the likelihood of marital cutoff. The higher the marital conflict, the higher is the emotional reactivity. Kerr and Bowen saw a) the husband’s marital reactivity as connected to feeling unloved, pressured to change, and unappreciated and b) the wife’s marital reactivity as connected to feeling unloved, ignored, and taken for granted. As a spouse increases awareness and control of their own emotional reactivity, emotional cutoff is reduced. The more we understand, the less we react. The emotional rainbow of reactivity may look very different in marital cutoff from “bitter rage to lingering sadness, from abrupt rejection to imperceptible distancing, from vivid intensity to apparent indifference.” Distant, formal marriages produce cutoff that looks different than the cutoff found in highly intense, fused marriages. The essence of marital cutoff is reactive conflict avoidance, and rigid repetitive homeostatic thinking and behaviour.[89]

Reactivity is the opposite of thoughtful responsiveness where one retains the power of choice. Emotional reactivity in married couples is associated with rigid inflexibility and demanding the other person to change. When reactivity takes over, we lose a sense of proportion, such as when to drop an argument. In our reactivity, we end up trying to control our spouse in order to regain our sense of personal control. Bowen emphatically said that one of the greatest diseases of humanity is to try to change a fellow human being.[90] Our futile attempt to change our spouse indicates self-serving nonacceptance, which will likely be resisted on principle. The more that we reactively push our spouse to change, the more likely is marital cutoff. Changing emotional reactivity in a married couple is a long process. The more differentiated we are, the less urgent is this desire to change our spouse. To know the blessing and telos of creation frees us from both the frantic pursuit of controlling our spouse and the opposite danger of reactively escaping our spouse through distance and cutoff. Many nowadays are attempting through techne and gnostic religion to escape from their bodies, their spouses, and creation itself.[91]

The single greatest impediment to understanding one another is our tendency to become emotionally reactive. Sometimes a spouse, who is not feeling listened to, will anxiously chase their spouse until they get a reaction. The rugged individualist’s determination to be independent often stems more from his reactivity to other people than from a thoughtfully determined direction for self. Rugged individualism and compliance are often two sides of the same marital reactivity.[92]

Behind our stubborn reactivity is the fear of loss of self, that we will be swallowed up and disappear. Such reactive fear causes us to maritally cut off rather than become a non-person. We reactively see ourselves as victimized by our stubborn, unloving, illogical spouse.[93] Ellen Benswanger observed that emotional cutoffs perpetuate the dichotomy of good / bad, rejector / rejectee, and victim / victimizer. We often see ourselves as having been treated unfairly, and we are not going to give in. Marital cutoff often brings emotional stuckness, denial of issues, frozen anger, and conflict avoidance. Bridging marital cutoff reduces hostility and blame of our spouse. As we accept appropriate responsibility for our life, we decrease the marital cutoff linked to our victim identity.[94]

Marital reactivity is like an auto-immune dysfunction. The pastoral coach has the potential to function as an immunological system. By being nonreactive and focusing on marital strengths, we set the emotional thermostat in the room.[95] By being nonreactive with married couples, the pastoral coach functions as a catalyst or enzyme for change and bridging marital cutoff. The pastoral coach also incarnationally models the process of nonreactivity in a way that can give a template to the couple.

What limits us as pastors from being nonreactive in our ministry to married couples? Perhaps it is the vicious cycle of our personal emotional reactivity which limits our ability to think clearly, which then limits our ability to be nonreactive with couples. In order to best help married couples, we need to become more aware of our own personal reactivity and our own tendency to cutoff. Undertaking a comprehensive guided self-examination is vital for pastoral coaching. It can be very difficult to see our own defensiveness. Being counter-intuitive can sometimes help with responding to emotional reactivity. Rather than fight a couple’s reactive blocking, the pastoral coach can initially concur with their marital assessment and nonanxiously explore the emotional content of their claimed non-reactivity.[96]

Married couples may sabotage our nonreactivity as pastoral coaches to see if we really ‘love them’ enough to emotionally fuse with their pseudo-selves. Some will even react to any suggestion of nonreactivity, claiming that their feelings are being disregarded and invalidated. If we stay on track, the reactivity and sabotage will die down. Time is on our side when we do not emotionally fuse with the married couple. One of our best ways to stay nonreactive with couples is to good-naturedly say no to “the urgent, important and serious”. Our nonreactivity to a married couple’s reactivity is vital in reducing marital cutoff.

1h) Emotional Cutoff and Process Questions

Emotional cutoff is reduced through thoughtful Family Systems process questions. Unlike many family therapy pioneers, Bowen was not a technique-oriented pragmatist. He was exceptionally disinterested in techniques. Titelman said that Bowen was anti-technique. The use of process questions is as close as Bowen came to a technique.[97] There is much ambiguity in Family Systems Thinking regarding its either having few techniques vs. having the most important technique vs. having no techniques at all. This makes it particularly challenging for other Family Therapists to figure out how Family Systems Theory works. Syncretistic attempts to blend Bowen Theory with other counseling practices often leave the counselor confused and frustrated.[98]

Process questions with married couples include “Who? What? Where? When? and How?” The ‘reducing cutoff’ benefits of process questions are that they help explore the space between the couple, slow down and diminish reactivity, and encourage self-reflective thoughtfulness. Psychoanalytic theory concentrates on the why of human actions. Asking why is a much less helpful question to ask, as it leads to cause-and-effect thinking.[99] Bowen Theory carefully avoids our automatic preoccupation with why something may have happened in a marriage. To introduce ‘why thinking’ into systems thinking brings about a reversion to conventional theory. Family Systems thinking focuses on what one does, and not on his / her verbal explanations about why he / she does it. The use of ‘why’ questions cause us to lose our focus on the relationship of the couple. ‘Why questions’ in marriage are often avoidance behaviour.[100] It is not easy to give up asking about the motivation, the why question. Why, one might ask, is it so hard to stop asking why? Asking ‘why’ seems to be a residual, regressive reaction when we are traumatized and grieved. ‘Why’ questions are usually simulated thinking, expressing emotional fusion over something that we are angry and anxious about. ‘Why’ sometimes screams within us, yet answers rarely satisfy the ache.

Insightful questions help protect the pastoral coach from acting like a dependency-causing expert / rescuer with couples. Bailing others out does not strengthen marriages. The pastoral coach is not called to save or change another person’s marriage. Thoughtful questions leave the couple in their own quandary, thereby allowing them to potentially own their own marital process. Friedman observed that 80% of his Family Systems Theory counseling was asking questions.[101] The coach, said Bowen, is always in control of the sessions, asking hundreds of questions and avoiding interpretations. One of the opening questions is usually to ask the couple what they want to work on. Questions are intended to be low-key and calm. Rather than being advice-giving, process questions help the married couple see their role in the emotional system. If the process questions do not neutrally connect with the couple’s emotionality, marital learning is limited. The more thoughtful the questions, the more effective is the bridging of cutoff through detriangling.[102]

Bowen used nonconfrontational questions to avoid taking marital sides. His goal was to stimulate thinking more than to encourage expression of feelings. Bowen Theory has conceptualized the human as a scientific creature that also feels.[103] When feelings or tears emerged, Bowen encouraged the coach to calmly ask “what was the thought that stimulated the tears, or asking the other what they were thinking when the feeling started.”[104] Frost, in a recent North Shore interview, said:

I think that one of the misunderstandings of Bowen Theory is that it has nothing to do with feelings or that you eliminate feelings or something. At one clinical conference, Bowen declared: “Feelings are the heartland of therapy.” So if you read carefully what he has to say about differentiation, he talks about the integration of the differentiation between the thinking and feeling and emotional systems. The idea is that you can’t really integrate something unless there is a degree of separation, so that you know the difference between when you are operating out of your feeling system and when you are operating out of your cognitive thinking system. Once you are able to tell the difference, then you can integrate them and have access to both. You are aware of your feelings, and at times you might want to go with your feelings. But you also have the counterbalance of the more objective thinking process that you can call on when it is important.[105]

Friedman described this use of questions as being a catalyst, enabling the couple to “bounce off” the coach to each other. Process questions bridge cutoff by reducing the married couple’s reactive anxiety, increase their self-awareness, and enable them to think more clearly. They help us to have a non-anxious presence, and to self-differentiate. The pastoral coach needs to hold his / her questions lightly. Process questions help us overcome the denial that affects married couples. When the questions are paradoxical and mischievous, unexpected morphogenesis and cutoff reduction may occur.[106]

1i) Emotional Cutoff and Over / Under-Functioning

Both overfunctioning and underfunctioning increase the likelihood of emotional cutoff. Therapists sometimes joke that every overfunctioner deserves his / her underfunctioner. With married couples, one is often an overfunctioner and the other a dependent underfunctioner, with reciprocal intensity depending on the floating anxiety in the emotional system. Bowen called this the overadequate-inadequate reciprocity. Almost every relationship is affected by the over / underfunctioning dynamic. Bowen said that overfunctioners can end “being pinned down in the one-up position.” Marital overfunctioners tend to feel trapped by their ‘shoulds’ while underfunctioners tend to feel trapped by their ‘cant’s’.[107]

Over-functioning is about doing too much to gratify one’s need to be somebody. Such ‘do-er’ people have a magnetic appeal to underfunctioners. Unless a pastoral coach learns to stop overfunctioning, this overfunctioning ‘helpfulness’ will be unhelpful, creating functional helplessness in the married couple. Bowen said in order to reduce marital helplessness, the pastoral coach is to “find a leader in the leaderless family.” Overfunctioning may cause ‘dis-integr-ation’ in the underfunctioners, inducing auto-destruction. The over / underfunctioning dynamic can even flare up unexpectedly in marital violence.[108]

It is vital that we turn the married couple into the systems specialists so that they don’t need us when future anxiety inevitably hits their emotional system. As pastoral coaches, we may find ourselves pressured to unwisely accept responsibility for insoluble marital problems. But if overfunctioners accept responsibility for the couple’s solutions, then they must also accept responsibility for the outcome of their conflict.[109] If a pastoral coach accepts responsibility for the anxiety of the married couple, they are actually being uncaring and robbing the couple of their opportunity for growth. Pastoral coaches are to promise no benefits except those which come from the couple’s own effort to learn about themselves and change themselves. The couple responds best when the pastoral coach is clear about what he / she can or cannot do. By matching people’s energy, the coach encourages the couple to accept responsibility for their own change. Overfunctioning by pastoral coaches increases the possibility of the coach’s own dysfunctioning and even burnout.[110] We overfunctioners must either willingly let go of overresponsibility or its very weight will force us to do so.

Nothing fuses married couples like one spouse over-functioning in the other’s space, whereas nothing creates emotional space like self-definition. Overfunctioning brings emotional death to our spouse.[111] Bowen holds that “…recovery can begin with the slightest decrease of the overfunctioning…” It is much easier to get the overfunctioner to reduce their overfunctioning than the other way around. A key in reducing marital cutoff is in making oneself small. This can include more self-effacing humour, more balance in being and doing, more peaceful presence, more honesty, more developing of character and virtue, more safe silences, more playful adventure, more creative dating, and less pressuring each other to conform to one’s expectations.[112]

Our post-modern context simultaneously marginalizes marriages and raises marital expectations. When a couple has unrealistic expectations of themselves, it fosters unhealthy conflict. These can include the expectation that one spouse has to preserve the peace and harmony, or the expectation that one spouse knows what is best for the other spouse. People nowadays are sometimes pressuring their own spouse to function in superhuman, godlike ways.[113] This can lead to an “anxious hovering” which impairs the other spouse’s ability to function. We will stop overfunctioning when we become accountable for the self and only for the self, communicate for the self and only for the self.[114] Reduction of over- and under-functioning is indispensable in lasting reduction of marital cutoff.

1j) Emotional Cutoff and Divorce

Cutoff among married couples is so common that it is almost the air we breathe. For many of us, marital and relational apartheid (the state of apartness and separation) is all that we generationally know. We may dislike it, but there seems no escape. The three marital symptoms that Friedman encouraged us to pay close attention to were distance, divorce, and conflict. Sometimes all three converge together relationally, with marital conflict often resulting in divorce and geographic/emotional distance. Marital estrangement is often a sign of the intensity of unresolved marital attachment.[115] Cutoff and divorce-related distance can be connected to the anxiety of emotional fusion and resulting loss of self. While there is loss of self in emotional fusion, there is also significant loss of self in the emotional cutoff connected with divorce. The inability of the couple to find a balance between closeness and personal space may predispose them to marital cutoff. Divorce, said Ferrera, is a complex, emotionally intense, multidimensional, multigenerational process. Part of the stress of divorce is that both marital partners rarely agree that divorce is necessary. The one withdrawing from the marriage may have different reactions from the one pursuing. The avoider can always outrun the marital pursuer. Marital cutoff tends to be generationally repetitive. Relational runners tend to keep on compulsively running. Runaway reactivity and unstable triangles go together. Those who run away from their own family will tend to run away in the marriage.[116]